Welcome to Object-Oriented

- Introduce complexity and object-oriented programming

- Introduce namespaces for grouping an application's identifiers

- Write our first object-oriented program

The technique of mastering complexity has been known since ancient times: divide et impera (divide and rule)" (Dijkstra, 1979)

Modern software applications are intricate, dynamic and complex. The number of lines of code can exceed the hundreds of thousands or millions. These applications evolve over time. Some take years of programming effort to mature. Creating such applications involves many developers with different levels of expertise. Their work consists of smaller stand-alone and testable sub-projects; sub-projects that are transferrable, practical, upgradeable and possibly even usable within other future applications. The principles of software engineering suggest that each component should be highly cohesive and that the collection of components should be loosely coupled. Object-oriented languages provide the tools for implementing these principles.

C++ is an object-oriented programming language specifically designed to provide a simple, comprehensive feature set for programming modern applications without loss in performance. C++ combines the efficiencies of the C language with the object-oriented features necessary for the development of large applications.

Addressing Complexity

Large applications are complex. We address their complexity by identifying the most important features of the problem domain; that is, the area of expertise that needs to be examined to solve the problem. We express the features in terms of data and activities. We identify the data objects and the activities on those objects as complementary tasks.

Consider a course enrollment system for a program in a college or university. Each participant

- enrolls in several face-to-face courses

- enrolls in several hybrid courses

- earns a grade in each course

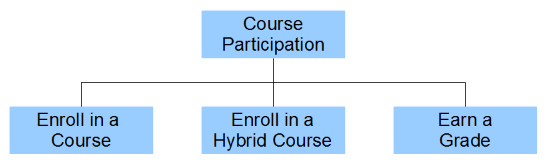

The following structure diagram identifies the activities.

If we switch our attention to the objects involved, we find a Course and a Hybrid Course. Focusing on a Course, we observe that it has a Course Code. We lookup the Code in the institution's Calendar to determine when that Course is offered.

We say that a Course has a Code and uses a Grading Scheme and that a Hybrid Course is a kind of Course. The diagram below shows these relationships between the objects in this problem domain. The connectors identify the types of relationships. The closed circle connector identifies a has-a relationship, the open circle connector identifies a uses-a relationship and the arrow connector identifies an is-a-kind-of relationship.

In switching our attention from the activities in the structure chart to the objects in the relationship diagram we have switched from a procedural description of the problem to an object-oriented description.

These two complementary approaches to mastering complexity date at least as far back as the ancient Greeks. Heraclitus viewed the world in terms of process, while Democritus viewed the world in terms of discrete atoms.

Learning to divide a complex problem into objects and to identify the relationships amongst the objects is the subject matter of system analysis and design courses. The material covered in this course introduces some of the principal concepts of analysis and design along with the C++ syntax for implementing these concepts in code.

Programming Languages

Eric Levenez maintains a web page that lists the major programming languages throughout the world. Many of these languages are object orientated.Java, C, C++, Python and C# are currently in top ten most popular languages. Java, C, C++ and C# have much syntax in common: Java syntax is C-like, but not a superset of C, C++ contains almost all of C as a subset, and C# syntax is C++-like but not a superset of C. Each is an imperative language; that is, a language that specifies every step necessary to reach a desired state.

The distinguishing features of C, C++ and Java are:

- C has no object-oriented support. C leaves us no choice but to design our programming solutions in terms of activity-oriented structures.

- C++ is hybrid. It augments C with object-oriented features. C++ lets us build our solutions partly from activities and partly from objects. The main function in any C++ program is a C function, which is not object-oriented. C++ stresses compile-time logic.

- Java is purely object-oriented. It excludes all non-object-oriented features. Java leaves us no choice but to design our solutions using an object-oriented structures.

Features of C++

Using C++ to learn object-oriented programming has several advantages for a student familiar with C. C++ is:

- nearly a perfect superset of C

- a multi-paradigm language

- procedural (can focus on distinct activities)

- object-oriented (can focus on distinct objects)

- realistic, efficient, and flexible enough for demanding projects

- large applications

- game programming

- operating systems

- clean enough for presenting basic concepts

- comprehensive enough for presenting advanced programming concepts

Type Safety

Type safety in central to C++.

A type-safe language traps syntax errors at compile-time, diminishing the amount of buggy code that escapes to the client. C++ compilers use type rules to check syntax and generate errors or warnings if any type rule has been violated.

C compilers are more tolerant of type errors than C++ compilers. For example, a C compiler will accept the following code, which may cause a segmentation fault at run-time:

#include <stdio.h>

void foo();

int main(void)

{

foo(-25);

}

void foo(char x[])

{

printf("%s", x); /* ERROR */

}

Output

Segmentation Fault (coredump)

The prototype for foo() instructs the compiler to omit checking for argument/parameter type mismatches. The argument in the function call is an int of negative value (-25) and the type received in the parameter is the address of a char array. Since the parameter's value is an invalid address, printing from that address causes a segmentation fault at run-time, but no error at compile-time.

We can fix this easily. If we include the parameter type in the prototype as shown below, the compiler will check for an argument/parameter type mismatch and issue an error message like that shown on the right:

#include <stdio.h>

void foo(char x[]);

int main(void)

{

foo(-25);

}

void foo(char x[])

{

printf("%s", x);

}

Output

Function argument assignment between types "char*" and "int" is not allowed.

Bjarne Stroustrup, in creating the C++ language, decided to close this loophole. He mandated that in C++ all prototypes list their parameter types, which has forced all C++ compilers to check for argument/parameter type mismatches at compile-time.

Namespaces

In applications written simultaneously by several developers, chances are high that some developers will use the same identifier for different variables in the application. If so, once they assemble their code, naming conflicts will arise. We avoid such conflicts by developing each part of an application within its own namespace and scoping variables within each namespace.

A namespace is a scope for the entities that it encloses. Scoping rules avoid identifier conflicts across different namespaces.

We define a namespace as follows:

namespace identifier {

}

The identifier after the namespace keyword is the name of the scope. The pair of braces encloses and defines the scope.

For example, to define x in two separate namespaces (english and french), we write

namespace english {

int x = 2;

// ...

}

namespace french {

int x = 3;

// ...

}

To access a variable defined within a namespace, we precede its identifier with the namespace's identifier and separate them with a double colon (::). We call this double colon the scope resolution operator.

For example, to increment the x in namespace english and to decrement the x in namespace french, we write:

english::x++;

french::x--;

Each prefix uniquely identifies each variable's namespace.

Namespaces hide their entities. To expose an identifier to the current namespace, we insert the using declaration into our code before referring to the identifier.

For example, to expose one of the x's to the current namespace, we write:

using french::x;

After which, we can simply write:

x++; // increments french::x but not english::x

To expose all of a namespace's identifiers, we insert the using directive into our code before referring to any of them.

For example, to expose all of the identifiers within namespace english, we write:

using namespace english;

Afterwards, we can write:

x++; // increments english::x but not french::x

Exposing a single identifier or a complete namespace simply adds the identifier(s) to the hosting namespace.

Common Usage

By far the most common use of namespaces is for classifying

- struct-like types

- function types

FIRST EXAMPLES

From C to C++ Syntax

To compare C++ syntax with C syntax, consider a program that displays the following phrase on the standard output device

Welcome to Object-Oriented

C - procedural code

The C source code for displaying this phrase is

// A Language for Complex Applications

// welcome.c

//

// To compile on linux: gcc welcome.c

// To run compiled code: a.out

//

// To compile on windows: cl welcome.c

// To run compiled code: welcome

//

#include <stdio.h>

int main(void)

{

printf("Welcome to Object-Oriented\n");

}

The two functions - main() and printf() - specify activities. These identifiers share the global namespace.

C++ - procedural code

The procedural C++ source code for displaying the phrase is

// A Language for Complex Applications

// welcome.cpp

//

// To compile on linux: g++ welcome.cpp

// To run compiled code: a.out

//

// To compile on windows: cl welcome.cpp

// To run compiled code: welcome

//

#include <cstdio>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

printf("Welcome to Object-Oriented\n");

}

The file extension for any C++ source code is .cpp. <cstdio> is the C++ version of the C header file <stdio.h>. This header file declares the prototype for printf() within the std namespace. std denotes standard.

The directive

using namespace std;

exposes all of the identifiers declared within the std namespace to the global namespace. The libraries of standard C++ declare most of their identifiers within the std namespace.

C++ - hybrid code

The object-oriented C++ source code for displaying our welcome phrase is

// A Language for Complex Applications

// welcome.cpp

//

// To compile on linux: g++ welcome.cpp

// To run compiled code: a.out

//

// To compile on windows: cl welcome.cpp

// To run compiled code: welcome

//

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main ( ) {

cout << "Welcome to Object-Oriented" << endl;

}

The object-oriented syntax consists of:

The directive

#include <iostream>inserts the

<iostream>header file into the source code. The<iostream>library provides access to the standard input and output objects.The object

coutrepresents the standard output device.

The operator

<<

inserts whatever is on its right side into whatever is on its left side.

- The manipulator

endl

represents an end of line character along with a flushing of the output buffer. Note the absence of a formatting string. The cout object handles the output formatting itself.

That is, the complete statement

cout << "Welcome to Object-Oriented" << endl;

inserts into the standard output stream the string "Welcome to Object-Oriented" followed by a newline character and a flushing of the output buffer.

First Input and Output Example

The following object-oriented program accepts an integer value from standard input and displays that value on standard output:

// Input Output Objects

// inputOutput.cpp

//

// To compile on linux: g++ inputOutput.cpp

// To run compiled code: a.out

//

// To compile on windows: cl welcome.cpp

// To run compiled code: welcome

//

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int i;

cout << "Enter an integer : ";

cin >> i;

cout << "You entered " << i << endl;

}

Output

Enter an integer : 65

You entered 65

The object-oriented input statement includes:

- The object

cin

represents the standard input device.

The extraction operator

>>

extracts the data identified on its right side from the object on its left-hand side.

Note the absence of a formatting string. The cin object handles the input formatting itself.

That is, the complete statement

cin >> i;

extracts an integer value from the input stream and stores that value in the variable named i.

The type of the variable i defines the rule for converting the text characters in the input stream into byte data in memory. Note the absence of the address of operator on i and the absence of the conversion specifier, each of which is present in the C language.

SUMMARY

- object-oriented languages are designed for solving large, complex problems

- object-oriented programming focuses on the objects in a problem domain

- C++ is a hybrid language that can focus on activities as well as objects

- C++ provides improved type safety relative to C

- cout is the library object that represents the standard output device

- cin is the library object that represents the standard input device

<<is the operator that inserts data into the object on its left-side operand>>is the operator that extracts data from the object on its left-side operand

EXERCISES

Read Wikipedia on the C++ Programming Language

Read this interview with Bjarne Stroustrup

"Be adventurous in your experimentation and somewhat more cautious in your production code. On my home pages, I have a "Technical and Style FAQ" that gives many practical hints and examples. However, to really develop significant new skills, one must read articles and books. I think of C++ as a multi-paradigm programming language. That is, C++ is a language that supports several effective programming techniques, where the best solution to a real-world programming problem often involves a combination of these techniques. Thus, I encourage people to learn data abstraction (roughly, programming using abstract classes), object-oriented programming (roughly, programming using class hierarchies) and generic programming (roughly, programming using templates). Furthermore, I encourage people to look for combinations of these techniques rather than becoming fanatical about one of these paradigms because it happens to be a great solution to a few problems.

It is important to remember that a programming language is only a tool. Once you master the basic concepts of a language, such as C++, it is far more important to gain a good understanding of an application area and of the problem you are trying to solve than it is to study the minute technical details of C++. Good luck, and have fun with C++! "

Extract from the Linux Journal: Interview with Bjarne Stroustrup Posted on Thursday, August 28, 2003 by Aleksey Dolya

Install Visual Studio on your local computer

Ensure that your remote Linux account is operational