Overview of Polymorphism

- Code a complete program using polymorphic objects to solve a systems or business problem

- Describe the four different categories of polymorphism

"A type provides a protective covering that hides the underlying representation and constrains the way objects may interact with other objects" Cardelli, Wegner, 1985.

Polymorphism was perfected in object-oriented languages, but has roots in procedural languages. Polymorphism relies on a language's type system to distinguish different meanings for the same identifier. This ambiguity introduces flexibility and enables reusability of code.

This chapter describes the difference between monomorphic and polymorphic languages and the use of a type system to ensure consistency. This chapter also identifies the categories of polymorphism supported by object-oriented languages and reviews how C++ implements each category.

Languages

Programming languages evolved from untyped origins through monomorphic languages to polymorphic ones. Untyped languages support words of one fixed size. Assembly languages and BCPL are examples. Typed languages support regions of memory of different sizes distinguished by their type. Typed languages can be monomorphic or polymorphic. In a monomorphic language the type of an object, once declared, cannot change throughout the object's lifetime. Polymorphic languages relax this relation between the object's type and a region of memory by introducing some ambiguity. The type of a polymorphic object may change during its lifetime. This ambiguity brings object descriptions closer to natural language usage.

Monomorphic languages require separate code for each type of object. For instance, a monomorphic language requires the programmer to code a separate sort() function for each data type, even though the logic is identical across all types. Polymorphic languages, on the other hand, let the programmer code the function once. The language applies the programming solution to any type.

The C++ language assumes that an object is monomorphic by default, but lets the programmer override this default by explicitly identifying the object as polymorphic.

Type Systems

A type system introduces consistency into a programming language. It is the first line of defense against coding relationships between unrelated entities. Typically, the entities in the expressions that we code have some relation to one another. The presence of a type system enables the compiler to check whether such relations follow well-defined sets of rules. Each type in a type system defines its own set of admissible operations in forming expressions. The compiler rejects all operations outside this set. Breaking the type system exposes the underlying bit strings and introduces uncertainty in how to interpret the contents of their regions of memory.

A strongly typed language enforces type consistency at compile-time and only postpones type-checking to run-time for polymorphic objects.

The C++ language is a strongly typed language. It checks for type consistency on monomorphic objects at compile-time and on polymorphic objects at run-time.

Role of Polymorphism

A polymorphic language provides the rules for extending the language's type system. Compilers apply their language's type system to identify possible violations of that system. Not all type differences between entities are necessarily errors. Those differences that the language allows expose its polymorphism. That is, the polymorphic features of a language represent the admissible set of differences between types that the language as a polymorphic language supports.

Categories

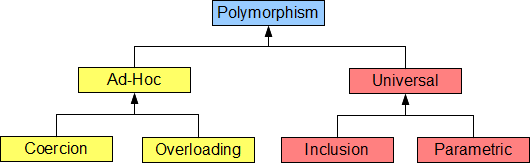

The polymorphic features that an object-oriented language supports can be classified into four categories. The C++ language supports all of these categories.

Classifications

Christopher Strachey (1967) introduced the concept of polymorphism informally into procedural programming languages by distinguishing functions that:

- Work differently on different argument types

- Work uniformly on a range of argument types

- He defined the former as ad-hoc polymorphism and the latter as parametric polymorphism:

"Ad-Hoc polymorphism is obtained when a function works, or appears to work, on several different types (which may not exhibit a common structure) and may behave in unrelated ways for each type. Parametric polymorphism is obtained when a function works uniformly on a range of types; these types normally exhibit some common structure." (Strachey, 1967)

Cardelli and Wegner (1985) expanded Strachey's distinction to accommodate object-oriented languages. They distinguished functions that:

- Work on a finite set of different and potentially unrelated types

- Coercion

- Overloading

- Work on a potentially infinite number of types across some common structure

- Inclusion

- Parametric

Inclusion polymorphism is specific to object-oriented languages.

Ad-Hoc Polymorphism

Ad-hoc polymorphism is apparent polymorphism. Its polymorphic character disappears at closer scrutiny.

Coercion

Coercion addresses differences between argument types in a function call and the parameter types in the function's definition. Coercion allows convertible changes in the argument's type to match the type of the corresponding function parameter. It is a semantic operation that avoids a type error.

If the compiler encounters a mismatch between the type of an argument in a function call and the type of the corresponding parameter, the language allows conversion from the type of the argument to the type of the corresponding parameter. The compiler inserts the code necessary to perform the coercion. The function definition itself only ever executes on one type - the type of its parameter.

Coercion has two possible variations:

- Narrow the argument type (narrowing coercion)

- Widen the argument type (promotion) For example,

// Ad-Hoc Polymorphism - Coercion

// coercion.cpp

#include <iostream>

// One function definition:

void display(int a) {

std::cout << "One argument (" << a << ')';

}

int main( ) {

display(10);

std::cout << std::endl;

display(12.6); // narrowing

std::cout << std::endl;

display('A'); // promotion

std::cout << std::endl;

}

One argument (10)

One argument (12)

One argument (65)

Coercion eliminates type mismatch or missing function definition errors. C++ implements coercion at compile time. If the compiler recognizes a type mismatch that is a candidate for coercion, the compiler inserts the conversion code immediately before the function call.

Most programming languages support some coercion. For instance, C narrows and promotes argument types in function calls so that the same function will accept a limited variety of argument types.

Overloading

Overloading addresses variations in a function's signature. Overloading allows binding of function calls with the same identifier but different argument types to function definitions with correspondingly different parameter types. It is a syntactic abbreviation that associates the same function identifier with a variety of function definitions by distinguishing the bindings based on function signature. The same function name can be used with a variety of unrelated argument types. Each set of argument types has its own function definition. The compiler binds the function call to the matching function definition.

Unlike coercion, overloading does not involve any common logic shared by the function definitions for functions with the same identifier. Uniformity is a coincidence rather than a rule. The definitions may contain totally unrelated logic. Each definition works only on its set of types. The number of overloaded functions is limited by the number of definitions implemented in the source code.

For example,

// Ad-Hoc Polymorphism - Overloading

// overloading.cpp

#include <iostream>

// Two function definitions:

void display() {

std::cout << "No arguments";

}

void display(int a) {

std::cout << "One argument (" << a << ')';

}

int main( ) {

display();

std::cout << std::endl;

display(10);

std::cout << std::endl;

}

No arguments

One argument (10)

Overloading eliminates multiple function definition errors. C++ implements overloading at compile time by renaming each identically named function as a function with its own distinct identifier: the language mangles the original identifier with the parameter types to generate an unique name. The linker uses the mangled name to bind the function call to the appropriate function definition.

Note that a procedural language like the C language does not admit overloading and requires a unique name for each function definition.

Universal Polymorphism

Universal polymorphism is true polymorphism. Its polymorphic character survives at closer scrutiny.

Unlike ad-hoc polymorphism, universal polymorphism imposes no restriction on the admissible types. The same function (logic) applies to a potentially unlimited range of different types.

Inclusion

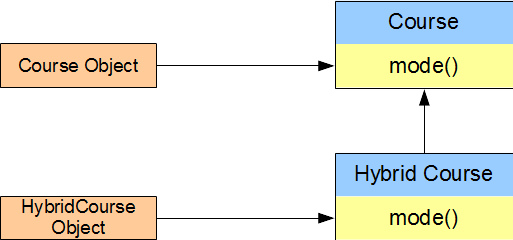

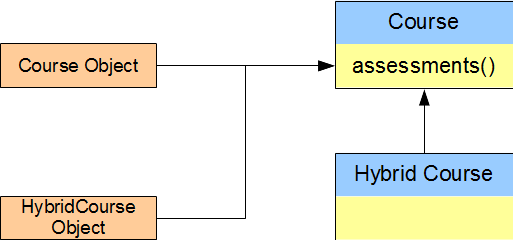

Inclusion polymorphism addresses the multiplicity of definitions available for a function call. Inclusion polymorphism allows the multiplicity of member function definitions by selecting the definition from the set of definitions based on the object's type. The type is a type that belongs to an inheritance hierarchy. The term inclusion refers to the base type including the derived types within the hierarchy. All member function definitions share the same name throughout the hierarchy.

In the figure below, both a HybridCourse and a Course belong to the same hierarchy. A HybridCourse uses one mode of delivery while a Course uses another mode. That is, a mode() query on a Course object reports a different result from a mode() query on a HybridCourse object.

Operations that are identical for all types within the hierarchy require only one member function definition. The assessments() query on a HybridCourse object invokes the same function definition as a query on the Course object. Defining a query for the HybridCourse class would only duplicate existing code and is unnecessary.

For example,

// Universal Polymorphism - Inclusion

// inclusion.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "Course.h"

using std::cout;

using std::endl;

int main( ) {

Course abc123("Intro to OO")

HybridCourse abc124("Intro to OO*");

cout << abc123.assessments() << endl;

cout << abc123.mode() << endl;

cout << abc124.assessments() << endl;

cout << abc124.mode() << endl;

}

Intro to OO 12 assessments

Intro to OO lecture-lab mode

Intro to OO* 12 assessments

Intro to OO* online-lab mode

Inclusion polymorphism eliminates duplicate logic across a hierarchy without generating missing function definition errors. C++ implements inclusion polymorphism at run-time using virtual tables.

Parametric

Parametric (or generic) polymorphism addresses differences between argument types in a function call and the parameter types in the function's definition. Parametric polymorphism allows function definitions that share identical logic independently of type. Unlike coercion, the logic is common to all possible types, without restriction. The types do not need to be related in any way. For example, a function that sorts ints uses the same logic as a function that sorts Students. If we have already written a function to sort ints, we only need to ensure that the Student class includes a comparison operator identical to that used by the sort function.

For example,

// Universal Polymorphism - Parametric

// parametric.cpp

#include <iostream>

template<typename T>

void sort(T* a, int n) {

int i, j;

T temp;

for (i = n - 1; i > 0; i--) {

for (j = 0; j < i; j++) {

if (a[j] > a[j+1]) {

temp = a[j];

a[j] = a[j+1];

a[j+1] = temp;

}

}

}

}

class Student {

int no;

// other data - omitted here

public:

Student(int n = 0) : no(n) {}

bool operator>(const Student& rhs) const {

return no > rhs.no;

}

void display(std::ostream& os) const {

os << no << std::endl;

}

};

int main( ) {

int m[] = {189, 843, 321};

Student s[] = {Student(1256), Student(1267), Student(1234)};

sort(m, 3);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

std::cout << m[i] << std::endl;

sort(s, 3);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++)

s[i].display(std::cout);

}

189

321

843

1234

1256

1267

Parametric polymorphism eliminates duplicate logic across all types without generating a missing function definition error. C++ implements parametric polymorphism at compile-time using template syntax.

Summary

- A polymorphic language allows type differences that a monomorphic type system would report as type errors.

- Polymorphic features are classified into four distinct categories.

- Ad-hoc polymorphism is only apparent - its polymorphic character disappears at closer scrutiny

- Coercion modifies an argument's type to suit the parameter type in the function definition

- Overloading associates the same function name with different and unrelated function definitions

- Universal polymorphism is true polymorphism - its polymorphic character survives at closer scrutiny

- Inclusion polymorphism selects a member function definition within an inheritance hierarchy based on an object's dynamic type

- Parametric polymorphism generates identical logic to match any object's type

Exercises

- Read Wikipedia on Types

- Read Wikipedia on Type-Safety

- Read Wikipedia on Polymorphism