Types, Overloading and References

- Review types, declarations, definitions and scoping

- Introduce overloading and function signatures

- Introduce pass by reference and compare it to pass by address

Correctness, simplicity, and clarity comes first" (Sutter, Alexandrescu, 2005)

Object-oriented languages inherit from their non-object-oriented predecessors the concepts of variable declarations, data types, data structures, logic constructs, and modular programming. The C++ language inherits these features from the C language (see IPC Notes for a detailed exposition).

This chapter elaborates on these inherited concepts and introduces the new concepts of references and overloading, which the C++ language adds to its C core. This chapter concludes with a section on arrays of pointers, which is important later in the design of polymorphic objects.

TYPES

The built-in types of the C++ language are called its fundamental types. The C++ language, like C, admits struct types constructed from these fundamental types and possibly other struct types. The C++ language standard refers to struct types as compound types. (The C language refers to struct types as derived types.)

Fundamental Types

The fundamental types of C++ include:

- Integral Types (store data exactly in equivalent binary form and can be signed or unsigned)

- bool - not available in C

- char

- int - short, long, long long

- Floating Point Types (store data to a specified precision - can store very small and very large values)

- float

- double - long double

bool

The bool type stores a logical value: true or false.

The ! operator reverses that value: !true is false and !false is true.

! is self-inverting on bool types, but not self-inverting on other types.

bool to int

Conversions from bool type to any integral type and vice versa require care. true promotes to an int of value 1, while false promotes to an int of value 0. Applying the ! operator to an int value other than 0 produces a value of 0, while applying the ! operator to an int value of 0 produces a value of 1. Note that the following code snippet displays 1 (not 4)

int x = 4;

cout << !!x;

Output:

1

Both C and C++ treat the integer value 0 as false and any other value as true.

Compound Types

A compound type is a type composed of other types. A struct is a compound type. An object-oriented class is also a compound type. To identify a compound type we use the keywords struct or class. We cover the syntax for classes in the following chapter.

For example,

// Modular Example

// Transaction.h

struct Transaction {

int acct; // account number

char type; // credit 'c' debit 'd'

double amount; // transaction amount

};

The C++ language requires the keyword identifying a compound type only in the declaration of that type. The language does not require the keyword struct or class in a function prototype or an object definition. Note the first code snippet below. Recall that the C language requires the keyword struct throughout the code as listed in the code snippet for C example below.

C++ example

// Modular Example - C++

// Transaction.h

struct Transaction {

int acct;

char type;

double amount;

};

void enter(Transaction*);

void display(const Transaction*);

// ...

int main() {

Transaction tr;

// ...

}

C example

// Modular Example - C

// Transaction.h

struct Transaction {

int acct;

char type;

double amount;

};

void enter(struct Transaction*);

void display(const struct Transaction*);

// ...

int main() {

struct Transaction tr;

// ...

}

auto Keyword

The auto keyword was introduced in the C++11 standard. This keyword deduces the object's type directly from its initializer's type. We must provide the initializer in any auto declaration.

For example,

auto x = 4; // x is an int that is initialized to 4

auto y = 3.5; // y is a double that is initialized to 3.5

auto is quite useful: it simplifies our coding by using information that the compiler already has.

DECLARATIONS AND DEFINITIONS

Modular programming can result in multiple definitions. To avoid conflicts or duplication, we need to design our header and implementation files accordingly. The C++ language distinguishes between declarations and definitions and stipulates the one-definition rule.

Declarations

A declaration associates an entity with a type, telling the compiler how to interpret the entity's identifier. The entity may be a variable, an object or a function.

For example, the prototype

int add(int, int);

declares add() to be a function that receives two ints and returns an int. This declaration does not specify what the function does; it does not specify the function's meaning.

For example, the forward declaration

struct Transaction;

declares Transaction to be of structure type. A forward declaration is like a function prototype: it tells the compiler how to interpret the entity's identifier. It tells the compiler that the entity is a valid type, but does not specify the entity's meaning.

Although a declaration does not necessarily specify meaning, it may specify it. Specifying a meaning is an optional part of any declaration.

Definitions

A definition is a declaration that associates a meaning with an identifier.

For example, the following definitions attach meanings to Transaction and to display():

struct Transaction {

int acct; // account number

char type; // credit 'c' debit 'd'

double amount; // transaction amount

};

void display(const Transaction* tr) { // definition of display

cout << "Account " << tr->acct << endl;

cout << (tr->type == 'd' ? " Debit $" : " Credit $") << endl;

cout << tr->amount << endl;

}

In C++, each definition is an executable statement. We may embed it amongst other executable statements.

For example, we may place a definition within an initializer:

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

//...

One Definition Rule

In the C++ language, a definition may only appear once within its scope. This is called the one-definition rule.

For example, we cannot define Transaction or display() more than once within the same code block or translation unit.

Declarations are not necessarily Definitions

Forward declarations and function prototypes are declarations that are not definitions. They associate an identifier with a type, but do not attach any meaning to that identifier. We may repeat such declarations several times within the same code block or translation unit.

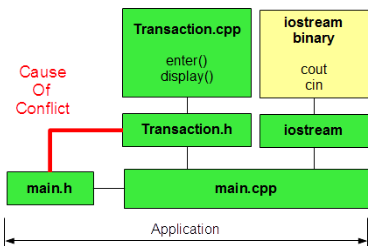

Header files consist of declarations. When we include several header files in a single implementation file, multiple declarations may occur. If some of the declarations are also definitions, this may result in multiple definitions within the same translation unit. Any translation unit must not break the one-definition rule. We need to design our header files to respect this rule.

Designing Away Multiple Definitions

A definition that appears more than once within the same translation unit generates a compiler error. Two solutions are shown below.

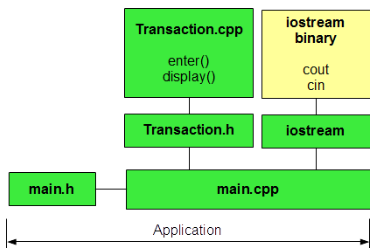

The program listed below consists of three modules: main, Transaction and iostream.

In the main module's implementation file we have introduced a new function called add(), which receives the address of a double and the address of a Transaction object. This function update the value stored in the first address:

// One Definition Rule

// one_defintion_rule.cpp

#include <iostream>

#include "main.h" // prototype for add()

#include "Transaction.h" // prototypes for enter() and display()

using namespace std;

int main() {

int i;

double balance = 0.0;

Transaction tr;

for (i = 0; i < NO_TRANSACTIONS; i++) {

enter(&tr);

display(&tr);

add(&balance, &tr);

}

cout << "Balance " << balance << endl;

}

void add(double* bal, const Transaction* tr) {

*bal += (tr->type == 'd' ? -tr->amount : tr->amount);

}

The Transaction module's header file defines the Transaction type:

// Modular Example

// Transaction.h

struct Transaction {

int acct; // account number

char type; // credit 'c' debit 'd'

double amount; // transaction amount

};

void enter(Transaction* tr);

void display(const Transaction* tr);

Design Question

Into which header file should we insert the prototype for this add() function?

If we insert the prototype into the main module's header file, main.cpp will not compile:

// main.h

#define NO_TRANSACTIONS 3

void add(double*, const Transaction*);

The compiler will report Transaction* as undeclared. Note that the compiler analyzes code sequentially and does not yet know what Transaction is when it encounters the prototype for add().

If we insert Transaction.h into this header file (main.h), we resolve this issue but break the one-definition rule in main.cpp:

// main.h

#define NO_TRANSACTIONS 3

#include "Transaction.h" // BREAKS THE ONE-DEFINITION RULE!

void add(double*, const Transaction*);

The main.cpp translation unit would contain TWO definitions of Transaction.

Possible designs are possible include:

- Forward Declaration Solution - insert the prototype into main.h

- Compact Solution - insert the prototype into Transaction.h

Forward Declaration Solution

Inserting the prototype into main.h along with a forward declaration of Transaction informs the compiler that this identifier in the prototype is a valid type.

// main.h

#define NO_TRANSACTIONS 3

struct Transaction; // forward declaration

void add(double*, const Transaction*);

This design provides the compiler with just enough information to accept the identifer, without exposing the type details.

Compact Solution

Inserting the prototype into the Transaction.h header file is a more compact solution:

// Modular Example

// Transaction.h

struct Transaction {

int acct; // account number

char type; // credit 'c' debit 'd'

double amount; // transaction amount

};

void enter(Transaction* tr);

void display(const Transaction* tr);

void add(double*, const Transaction*);

This design localizes all declarations related to the Transaction type within the same header file. We call functions that support a compound type the helper functions for that type.

Proper Header File Inclusion

To avoid contaminating system header files, we include header files in the following order:

#include < ... >- system header files#include " ... "- other system header files#include " ... "- your own header files

We insert namespace declarations and directives after all header file inclusions.

SCOPE

The scope of a declaration is the portion of a program over which that declaration is visible. Scopes include

- global scope - visible to the entire program

- file scope - visible to the source code within the file

- function scope - visible to the source code within the function

- class scope - visible to the member functions of the class

- block scope - visible to the code block

The scope of a non-global declaration begins at the declaration and ends at the closing brace for that declaration. A non-global declaration is called a local declaration. We say that an identifier that has been locally declared is a local variable or object.

Going Out of Scope

Once a declaration is out of its scope, the program has lost access to the declared variable or object. Identifying the precise point at which a variable's or object's declaration goes out of scope is important in memory management.

Iterations

In the following code snippet, the counter i, declared within the for statement, goes out of scope immediately after the closing brace:

for (int i = 0; i < 4; i++) {

cout << "The value of i is " << i << endl;

} // i goes out of scope here

We cannot refer to i after the closing brace.

A variable or object declared within a block goes out of scope immediately before the block's closing brace.

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

int j = 2 * i;

cout << "The value of j is " << j << endl;

} // j goes out of scope here

The scope of j extends from its definition to just before the end of the current iteration. j goes out of scope with each iteration. The scope of i extends across the complete set of iterations.

Shadowing

An identifier declared with an inner scope can shadow an identifier declared with a broader scope, making the latter temporarily inaccessible. For example, in the following program the second declaration shadows the first declaration of i:

// scope.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

int main() {

int i = 6;

cout << i << endl;

for (int j = 0; j < 3; j++) {

int i = j * j;

cout << i << endl;

}

cout << i << endl;

}

Output:

6

0

1

4

6

FUNCTION OVERLOADING

In object-oriented languages functions may have multiple meanings. Functions with multiple meanings are called overloaded functions. C++ refers to functions first and foremost by their identifier and distinguishes different meanings by differing parameter lists. For each identifier and parameter list combination, we implement a separate function definition. C++ compilers determine the definition to select by matching the argument types in the function call to the parameters types in the definition.

Function Signature

A function's signature identifies an overloaded function uniquely. Its signature consists of

- the function identifier

- the parameter types (ignoring const qualifiers or address of operators as described in references below)

- the order of the parameter types

type identifier ( type identifier [, ... , type identifier] )

The square brackets enclose optional information. The return type and the parameter identifiers are not part of a function's signature.

C++ compilers preserve identifier uniqueness by renaming each overloaded function using a combination of its identifier, its parameter types and the order of its parameter types. We refer to this renaming as name mangling.

Example:

Consider the following example of an overloaded function. To display data on the standard output device, we can define a display() function with different meanings:

// Overloaded Functions

// overload.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

// prototypes

void display(int x);

void display(const int* x, int n);

int main() {

auto x = 20;

int a[] = {10, 20, 30, 40};

display(x);

display(a, 4);

}

// function definitions

//

void display(int x) {

cout << x << endl;

}

void display(const int* x, int n) {

for (int i = 0; i < n; i++)

cout << x[i] << ' ';

cout << endl;

}

Output:

20

10 20 30 40

C++ compilers generate two one definition of display() for each set of parameters. The linker binds each function call to the appropriate definition based on the argument types in the function call.

Prototypes

A function prototype completes the function's signature by specifying the return type. However, the parameter identifiers are also optional in the prototype. The prototype provides sufficient information to validate a function call.

A prototype without parameter types identifies an empty parameter list. The keyword void, which the C language uses to identify no parameters is redundant in C++. We omit this keyword in C++.

Prototypes Required

A programming language may require a function declaration before any function call for type safety. The declaration may be either a prototype or the function definition itself. The compiler uses the declaration to check the argument types in the call against the parameter types in the prototype or definition. The type safety features of C++ require a preceding declaration.

For example, the following program will generate a compiler error (note that the absence of any printf declaration):

int main() {

printf("Hello C++\n");

}

To meet type safety requirements, we include the prototype:

#include <cstdio> // the prototype is in this header file

using namespace std;

int main() {

printf("Hello C++\n");

}

Default Parameter Values

We may include default values for some or all of a function's parameters in the first declaration of that function. The parameters with default values must be the rightmost parameters in the function signature.

Declarations with default parameter values take the following form:

type identifier(type[, ...], type = value);

The assignment operator followed by a value identifies the default value for each parameter.

Specifying default values for function parameters reduces the need for multiple function definitions if the function logic is identical in every respect except for the values received by the parameters.

Example:

For example,

// Default Parameter Values

// default.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void display(int, int = 5, int = 0);

int main() {

display(6, 7, 8);

display(6);

display(3, 4);

}

void display(int a, int b, int c) {

cout << a << ", " << b << ", " << c << endl;

}

Output:

6, 7, 8

6, 5, 0

3, 4, 0

Each call to display() must include enough arguments to initialize the parameters that don't have default values. In this example, each call must include at least one argument. An argument passed to a parameter that has a default value overrides the default value.

REFERENCES

A reference is an alias for a variable or object. Object-oriented languages rely on referencing. A reference in a function call passes the variable or object rather than a copy. In other words, a reference is an alternative to the pass by address mechanism available in the C language. Pass-by-reference code is notably more readable than pass-by-address code. To enable referencing, the C++ rules on function declarations are stricter than those of the C language.

The declaration of a function parameter that is received as a reference to the corresponding argument in the function call takes the form

type identifier(type& identifier, ... )

The & identifies the parameter as an alias for, rather than a copy of, the corresponding argument. The identifier is the alias for the argument within the function definition. Any change to the value of a parameter received by reference changes the value of the corresponding argument in the function call.

Comparison Examples

Consider a function that swaps the values stored in two different memory locations. The programs listed below compare pass-by-address and pass-by-reference solutions. The program on the left passes by address using pointers. The program on the right passes by reference:

Swapping values by address

// Swapping values by address

// swap1.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void swap ( char *a, char *b );

int main ( ) {

char left;

char right;

cout << "left is ";

cin >> left;

cout << "right is ";

cin >> right;

swap(&left, &right);

cout << "After swap:"

"\nleft is " <<

left <<

"\nright is " <<

right <<

endl;

}

void swap ( char *a, char *b ) {

char c;

c = *a;

*a = *b;

*b = c;

}

Swapping values by reference

// Swapping values by reference

// swap2.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

void swap ( char &a, char &b );

int main ( ) {

char left;

char right;

cout << "left is ";

cin >> left;

cout << "right is ";

cin >> right;

swap(left, right);

cout << "After swap:"

"\nleft is " <<

left <<

"\nright is " <<

right <<

endl;

}

void swap ( char &a, char &b ) {

char c;

c = a;

a = b;

b = c;

}

Clearly, reference syntax is simpler. To pass an object by reference, we attach the address of operator to the parameter type. This operator instructs the compiler to pass by reference. The corresponding arguments in the function call and the object names within the function definition are not prefixed by the dereferencing operator required in passing by address.

Technically, the compiler converts each reference to a pointer with an unmodifiable address.

ARRAY OF POINTERS

Arrays of pointers are data structures like arrays of values. Arrays of pointers contain addresses rather than values. We refer to the object stored at a particular address by dereferencing that address. Arrays of pointers play an important role in implementing polymorphism in the C++ language.

An array of pointers provides an efficient mechanism for processing the set. With the objects' addresses collected in a contiguous array, we can refer to each object indirectly through the pointers in the array and process the data by iterating on its elements.

In preparation for a detailed study of polymorphic objects later in this course, consider the following preliminary example:

Example:

// Array of Pointers

// array_pointers.cpp

#include <iostream>

using namespace std;

const int N_CHARS = 31;

struct Student {

int no;

double grade;

char name[N_CHARS];

};

int main() {

const int NO_STUDENTS = 3;

Student john = {1234, 67.8, "john"};

Student jane = {1235, 89.5, "jane"};

Student dave = {1236, 78.4, "dave"};

Student* pStudent[NO_STUDENTS]; // array of pointers

pStudent[0] = &john;

pStudent[1] = &jane;

pStudent[2] = &dave;

for (int i = 0; i < NO_STUDENTS; i++) {

cout << pStudent[i]->no << endl;

cout << pStudent[i]->grade << endl;

cout << pStudent[i]->name << endl;

cout << endl;

}

}

Output

1234

67.8

john

1235

89.5

jane

1236

78.4

dave

Here, while the objects are of the same type, the processing of their data is done indirectly through an array of pointers to that data.

KEYWORDS

The 84 keywords of the C++11 standard are listed below. We cannot use any of these keywords as identifiers. Those in bold are also C keywords. The italicized keywords are alternative tokens for operators.

| alignas | alignof | and | and_eq | asm | auto | bitand |

| itor | bool | break | case | catch | char | char16_t |

| char32_t | class | compl | const | constexpr | const_cast | continue |

| decltype | default | delete | do | double | dynamic_cast | else |

| enum | explicit | export | extern | false | float | for |

| friend | goto | if | inline | int | long | mutable |

| namespace | new | not | not_eq | noexcept | nullptr | operator |

| or | or_eq | private | protected | public | register | reinterpret_cast |

| return | short | signed | sizeof | static | static_assert | static_cast |

| struct | switch | template | this | thread_local | throw | true |

| try | typedef | typeid | typename | union | unsigned | using |

| virtual | void | volatile | wchar_t | while | xor | xor_eq |

C++ compilers will successfully compile any C program that does not use any of these keywords as identifiers provided that that program satisfies C++'s type safety requirements. We call such a C program a clean C program.

SUMMARY

- a bool type can only hold a true value or a false value

- C++ requires the struct or class keyword only in the definition of the class itself

- a declaration associates an identifier with a type

- a definition attaches meaning to an identifier and is an executable statement

- a definition is a declaration, but a declaration is not necessarily a definition

- the scope of a declaration is that part of the program throughout which the declaration is visible

- we overload a function by changing its signature

- a function's signature consists of its identifier, its parameter types, and the order of its parameter types

- a C++ function prototype must include all of the parameter types and the return type

- the

&operator on a parameter type instructs the compiler to pass by reference - pass by reference syntax simplifies the pass by address syntax in most cases

- an array of pointers is a data structure that provides an efficient way for iterating through a set of objects based on their current type